- Home

- Brian Klingborg

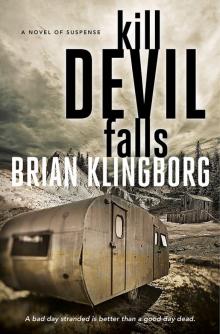

Kill Devil Falls Page 9

Kill Devil Falls Read online

Page 9

Frank stood in the front yard, a can of beer in his hand.

“Real nice night for a walk!” he yelled. “What happened to the lights?”

“Hell if I know,” Big Ed said.

“You want me and Mike to take a look at the marshal’s car now?” Frank asked.

“Not now, Frank,” Big Ed shouted. “Go on inside. We’ll come get you in a bit.”

Frank raised the beer in a salute. “Ten-four, Sheriff!”

Another thirty yards and they approached a two-story house, one of the largest Helen had seen in Kill Devil Falls. Like most plots in town, this one was unkempt and overgrown with weeds. A dented car was parked in a carport alongside the house.

“This is Lawrence’s grandma’s place,” Teddy said.

“Big house for one person,” Helen said.

“One thing we got plenty of up here is space,” Big Ed said.

“Should one of us go round back?” Teddy asked.

“We’ll just call him out. If he runs, he won’t get far.” Big Ed turned to Helen. “He’s a city boy.”

Helen didn’t take the bait. She side-stepped away from Big Ed and Teddy. No sense in making it easy for Lawrence if he was, in fact, a madman preparing to unleash a fusillade of bullets.

Big Ed set the lantern down on the ground in front of the porch, held the shotgun at port arms.

“Lawrence! This is Sheriff Scroggins. I need to talk to you. Come on out. And show me your hands when you walk through the front door.”

Silence. No sign of movement from within the house.

“Lawrence!”

Thirty seconds passed. Sixty.

“Don’t make me come in and get you!”

The front door slowly opened.

“Sheriff? What’s going on?” Lawrence’s voice quaked.

“Out on the porch, hands up.”

“What’s the matter? Did I do something wrong?”

“’Course not. Come on out, now.”

Lawrence shuffled forward.

“Closer,” Big Ed commanded. “Down here.”

Lawrence descended the porch steps. He was dressed in sweatpants, a T-shirt, and the same jean jacket Helen had seen him wearing in the restaurant. His feet were sockless, in flip-flops.

“On your knees, Lawrence.”

“Sheriff—”

“Shut your mouth and get on your knees.” Big Ed didn’t raise his voice, but the menace in his tone was tangible.

Lawrence slowly sank to his knees. Helen was uneasy. No need to treat Lawrence like a dangerous felon just yet.

Big Ed traced an arc around Lawrence and approached him from the rear.

“Cross your ankles and put your hands on top of your head.”

Lawrence did as ordered.

“Edward!” Big Ed tossed Teddy the shotgun. Teddy caught it, fumbled it, almost dropped it.

Big Ed cuffed Lawrence.

“Why you are arresting me?” Lawrence protested.

“I’m not. I just want to have a talk.” Big Ed pulled Lawrence to his feet. “Wait here,” he instructed. He walked over to Teddy, said in a low voice, “Have a quick look inside. I’ll meet you back at the jail.”

“Sheriff, please, what’s going on?” Lawrence quailed.

“I told you, I need a word. Now come along.”

He picked up the lantern, led Lawrence away. Helen turned to follow, but Teddy reached for her arm.

“You … you want to give me a hand?”

Helen figured she should go with the sheriff, participate in the questioning. For all she knew, Big Ed might chain Lawrence to the cell bars and start whipping him with a cat-o’-nine-tails. But Teddy looked forlorn. Scared.

“Sure, Teddy. But let’s make it quick.”

“Quick’s my middle name.”

“No sense in advertising that fact,” Helen said.

“Huh?”

“Nothing. Let’s go.”

8

HELEN STEPPED THROUGH THE front door, swept the foyer with her flashlight. Like Big Ed and Teddy’s house, this one featured a living room to the right, a staircase straight ahead. To the left was a doorway leading to the kitchen.

“US Marshals!” she called out. “Anyone inside this house? Come out where I can see you!”

Teddy pushed in behind her. She felt his hot breath on her neck. She walked into the living room, saw that it was devoid of furniture. Not even a scrap of carpet, a picture on the wall, nothing. Teddy waved his flashlight around the room.

“Guess he don’t spend much time in here,” Teddy said.

“Why don’t you check this floor?” Helen asked. “I’ll search upstairs.”

“Don’t you think we should stay together?” Teddy’s voice wavered a touch.

“Come on, Teddy. I don’t want to be here all night.” She entered the foyer, paused, turned back. “Remember, we don’t have authority to do a full search. If you find something, don’t touch it. We’ll have to come up with an excuse to get a warrant later. You understand?”

“Got it,” Teddy said.

“Okay.” She started for the stairs.

“Marshal?”

“Yes?”

“Rita was alive when you found her?”

“She was.” She pictured Rita gasping, her throat sliced open like an Easter ham.

“Did she … say anything? Something that might help us find out who did it?”

“No. I would have mentioned if she did.”

“Right.”

She couldn’t see him clearly in the dark, but heard the sound of his fingers scratching the bristly hairs of his beard.

“What a thing,” he said. “To die in the woods like that. Hands cuffed behind your back.”

Helen turned away. “Let’s get this done,” she snapped.

She climbed the stairs, her face flushed with anger. Teddy was right. It was a horrible way to die. And she partially blamed him, for convincing her to leave Rita unattended. But really, the fault was hers. Her idiotic decision to go to the Trading Post, to leave Rita cuffed. Her fault Rita was unable to defend herself when the killer came calling.

Helen set aside her feelings of guilt and remorse. She needed to remain sharp, focused. If the perp was still in Kill Devil Falls, she was going to take him down. Failing that, however, she wanted a solid piece of evidence. The murder weapon. Bloody clothes.

But she didn’t expect to find anything here. Lawrence wasn’t the killer. If she was sure of anything, it was that.

She raised her flashlight, found herself facing a hallway with doors leading off to the left and the right. She started opening them, one by one: An empty bedroom. Another bedroom, containing two single bed frames and a poorly aged chest of drawers. A supply closet holding a collection of ancient cleaning supplies and a desiccated mop.

Behind the last door on the right was a bathroom, currently in use, judging from the toothpaste and other items on the sink. Directly across from it was a furnished bedroom. She decided to check out the bedroom first.

The bedroom featured a queen bed with a nightstand along one wall, and a chest of drawers opposite. The furniture was heavy, solid wood, not the usual IKEA particleboard. Inherited from the grandmother, Helen guessed. Spread across the floor was a collection of books. Helen shoved them around with the toe of her boot, reading titles.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, by Nietzsche. Sun and Steel, by Mishima. The Collected Works of Guy de Maupassant. A thick comic book called Watchmen, which Helen recalled having been made into a movie. A couple of sci-fi titles. A photography book called Memento Mori.

She picked this one up, leafed through it. Inside were portraits dating back to the early years of daguerreotype photography. Two little girls in bonnets posed beside their infant brother. A skinny father in a somber black coat, a Rubenesque mother wearing a high-collared Victorian dress, a child seated between them.

All the people in the book looked terribly glum. In those days, a photo required a long exposure time, so e

veryone had to sit completely still for several minutes. No silly poses or goofy smiles.

But it was more than that—there was something off about these portraits. Helen turned a page, saw a small girl in a white dress, a wreath of flowers around the crown of her head, lying on a daybed, three siblings standing expressionlessly around her. Another of a woman seated on a loveseat, her teenaged daughter beside her, the girl’s head leaning awkwardly into the woman’s ample bosom, eyes staring listlessly off into space.

Helen flipped to the back cover, read the copy:

Memento Mori—“Remember that you will die.” The practice of photographing the recently deceased was popular in the nineteenth century, when death, especially that of infants and children, was commonplace. Photographs served as keepsakes of departed family members, and not only helped with the grieving process but often were the only visual representation of the deceased a family possessed. As such, they were highly valued and given a place of prominence in the household.

Eww, Helen thought. How morbid. She put the book back in the pile, wiped her hand on her pants.

Downstairs, in the kitchen, Teddy laid the shotgun on a small dining table, idly riffled through cupboards. Most were bare, apart from the belly-up corpses of cockroaches and a few ancient, petrified food crumbs. A plastic dish drainer containing chipped crockery rested beside the sink. Some stained coffee mugs were in one cupboard, a rack of ancient, stale-smelling spice bottles in another. A beat-up toaster oven sat on the counter, and in front of it, a set of keys. Teddy picked up the keys, put them in his jacket pocket.

He turned from the counter, noticed a pantry door set into the wall. He opened the door, directed his flashlight inside.

He saw a shelf lined with perhaps ten cereal boxes, all of them Cheerios. Another with ten canisters of Quaker Oatmeal. A third, two cases of Campbell’s alphabet soup. Five plastic containers of Slim Jims. A dozen boxes of oat and honey granola bars.

On the floor of the pantry were a dozen cases of Miller High Life and four bottles of Wild Turkey. Teddy snorted derisively. He shut the pantry door, retrieved the shotgun, continued through the kitchen to the back of the house.

Upstairs, Helen opened dresser drawers, pawed through shirts, pants, underwear, jeans. Lawrence’s wardrobe seemed to consist entirely of Old Navy casual apparel. She searched the closet. A coat and several button-down shirts dangled on wire hangers. She reached into the coat’s pockets, came up with loose change, a few receipts from a supermarket in Donnersville, a stale piece of gum. A gym bag lay on the floor. She unzipped it, gasped at the rank odor of stale sweat. Holding her breath, Helen dumped out the contents. Dirty shirts, pants, and other clothes. Lawrence’s laundry. She kicked the items back into the bag.

She opened the nightstand drawer. Inside were a pair of sunglasses, a fold-out pocket knife. A wallet. She flipped open the wallet, checked Lawrence’s driver’s license, took a photo of it with her cell phone. Aside from the license, there was an ATM card, a couple of credit cards, and about two hundred in cash. Neither a pittance nor a king’s ransom. Helen set the wallet down. She used her phone to take a photo of the fold-out knife, then shut the drawer.

She got down on all fours and shined her flashlight under the bed. Nothing but a loose sock and lots of dust bunnies.

She crossed the hall, entered the bathroom. On the sink were toothpaste, a toothbrush, a razor, shaving cream. The edge of the tub held shampoo, conditioner. A dark ring of grit circled the bottom of the tub. She leaned into the tub, inspected the grit closely with her flashlight, rubbed it with her finger. It looked like normal, everyday dirt and grease.

She opened the medicine cabinet. And finally, things got interesting. She used a finger to pick through a dozen plastic pill bottles. Aspirin, of course. As well as buprenorphine, clonazepam, diazepam, Percocet.

Teddy’s voice came from downstairs. “Marshal!”

She leaned out of the bathroom. “Yes?”

“I think you’re gonna want to see this.”

“Coming!”

Helen took a photo of the pill bottles, closed the cabinet. She hurried down the hallway, descended the stairs. Teddy waited below, slightly out of breath.

“This way,” he said.

He led Helen through the kitchen and into another room, perhaps once used as an office but now empty, and then beyond that to a mudroom. Lawrence apparently used the mudroom as his temporary garbage dump—half a dozen bags filled with empty food boxes, crushed beer cans, and drained bourbon bottles sat by a back door leading to an enclosed porch. An ancient green washing machine squatted open-mouthed in a corner like a fossilized bullfrog.

Teddy used his flashlight to pinpoint a door set into the back wall. The door was ajar.

“Cellar,” Teddy explained.

“What’s down there?”

“I think you need to see for yourself. I really can’t … can’t describe it.”

Helen felt a prick of apprehension. And annoyance. She scowled, stepped through the doorway. Cement steps led down into darkness. She smelled boiled meat, insect spray, and an unfamiliar acrid tang.

“What’s that smell?”

“You’ll see.” Teddy sounded almost gleeful.

Helen crept down the steps. She directed the beam of her flashlight around the perimeter of the room.

At first she saw nothing out of the ordinary. Stained cardboard boxes, a couple of old bicycles slouching on flat tires, broken furniture—the usual junk people stuff into their basements, closets, and attics.

In the room’s center was a long picnic table. A collection of shiny instruments winked and glinted. Helen moved closer.

She froze when her light revealed a pair of glowing eyes, a set of razor-sharp teeth. A woodland animal crouched on the table, looking straight at her. She slowly reached for her Glock.

The animal didn’t move. Just stared. Not a twitch or a ripple of its muscles. Not a blink of its eyes. She realized it was dead. Stuffed. Is this what Teddy wanted her to see? His idea of a joke?

The creature resembled a hedgehog—bristly fur, a round snout. A pair of miniature horns extended from the side of its head, conjuring up an image of a Viking helmet from a Wagner opera. The animal’s teeth were too big for its mouth—nasty-looking fangs curved downward below its chin.

“What the hell is that?” Helen said.

Teddy snort-laughed.

Another creature sat a foot away from the hedgehog-thing. This one was definitely a cat … of some sort. A cat standing on all fours. With a set of feathery wings unfurled from its haunches.

Helen suppressed an urge to run back up the stairs. She quickly shined her light across the rest of the cellar.

She spied a guinea pig on a folding wooden chair. Well, two guinea pigs. Joined seamlessly at the midsection, minus back legs, conjoined torsos and heads looking in opposite directions.

A Chihuahua’s head atop the body of a Papillon.

A fat little Dachshund, belly up, six legs arching from its sides, spider-like, reminding Helen of the scene in the director’s cut of The Exorcist where the little girl crabwalks down the stairs at the dinner party.

“Look here,” a voice whispered in her ear. Helen jumped. Teddy pointed his flashlight at a huge mass of black rats, tangled in a ball on the ground, their tails linked together in an unbreakable knot.

“I heard about this,” he said. “They call it a Rat King. The rats get all stuck together like that, try to run every which way, and eventually starve to death.”

Helen felt her gorge rise.

“What in God’s balls is going on down here?”

“They’re all taxidermied,” Teddy said.

He edged past her, focused his light on the table. Neatly laid out on its splintered wooden surface was a collection of tools, including scalpels, scissors, forceps, needles, catgut, and many other instruments that Helen didn’t recognize.

“He’s got all kinds of knives, needles, pliers, you name it.”

&nb

sp; Teddy spotlit a metal rack against the wall containing rows of chemical bottles, bags of stuffing, hundreds of orbs with round and slit pupils in a plastic container, boxes of fur and feathers.

“Hair, glass eyes, stuffing, chemicals for cleaning and tanning hides,” Teddy said.

“Where does he get the animals?”

“I found some carriers in the corner.” Teddy indicated a stack of plastic pet carriers and some cardboard boxes for transporting rodents. “My guess is he gets ’em at the ASPCA or a pet store.”

“He does this to them … I mean … he brings them here, uses them for these … projects?”

Teddy shrugged. “Guess so.”

“Let’s get the hell out of here.”

“Right behind you,” Teddy said.

Once outside, on the front lawn, Teddy pointed at the carport.

“Think we should have a look?”

“I want to get back to the jail, see if Lawrence said anything to the sheriff.” Helen kept imagining medieval torture scenes: Lawrence spread-eagled on a rack, Big Ed ratcheting the roller.

“It’ll just take a sec,” Teddy said. He jogged over to the car, an old Toyota, opened the driver’s side door. He laid the shotgun on the roof, ducked down, searched the front seats, foot wells, and glove compartment. Helen waited on the edge of the yard, hands in her pockets, huddled against the cold.

“Deputy, we need to get crime scene techs up here—let them do that.”

Teddy climbed out of the driver’s seat, opened the back door, crawled inside.

“If there is evidence in there, you’re contaminating it!” she yelled. She disapproved of Teddy’s lack of proper procedure, but figured it didn’t matter much in the end. He wasn’t going to find anything. Only a complete numbskull would commit murder, then toss the weapon into his own car. Especially with an entire forest in which to dump evidence.

Teddy shut the back door.

“Deputy,” Helen called.

“Hold on!” He opened the driver’s side door again, pulled the trunk release. He walked around to the back of the Toyota, shined his flashlight into the open trunk.

Kill Devil Falls

Kill Devil Falls